Poverty, Prosperity, & Partnership: Moving from aid to innovation ... transaction to transformation10/5/2020  Having been associated with global development and relief aid programs in some way for over 33 years, I have seen individuals and communities respond to long term help in decreasingly positive ways over time. Much has been written about how aid hurts rather than helps and development programs create dependency. To a degree these statements are correct, if done incorrectly. Billions of dollars have been spent to build infrastructures for aid, including distribution networks, equipment, local and global staffing, food/medicine/technology aid materials equipment and supplies. Have people been helped? Absolutely. Have they been harmed? Yes. The relief and development community has unfortunately in many cases, over time, put programs, process, and funding ahead of people. This is not to say we must stop doing relief and development, i.e. throw the proverbial baby out with the bath water. There will always be a need for emergency relief and aid due to natural and human disasters and catastrophic weather events. It is just that we must not continue to use expensive existing delivery systems and processes, and we must first consider where we can use the local human capacity, the human potential that is available even in the midst of human suffering... You can download the entire white paper below:

David L. NeelyDavid is Operations and Outreach Pastor for Blue Valley Baptist Church in Overland Park, Kansas. He and his wife Phyllis have three daughters.. David holds a B.S. in Education from the University of Oklahoma. He studied evangelism and missions at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary prior to receiving a M.A. in Interdisciplinary Studies at Trinity Theological Seminary.

0 Comments

A couple of years ago I had the privilege of going on a ministry vision trip with Dr. Dane Fowlkes, Co-founder of The Unfinished Task Network, to the country of Iraq. While there, we are able to look out over the Nineveh plains. What a blessing it was to see the very place where Jonah ended up after running from God. As I consider the many indigenous pastors I know in East and West Africa, India, and Thailand, I understand the difficulties, frustrations, loneliness, and isolation they must feel at times, especially during these days dealing with drought in some areas, flooding in other areas, and the impact of COVID-19 all over the world. Throw in civil unrest and government corruption, and you can see why pastors may be overwhelmed, frightened, and even feel like giving up. I want to encourage my fellow pastors and church planters. The Bible contains many stories of great struggle, perseverance, and triumph. Noah spent one-hundred years faithfully building the ark to save the human family. Abraham was a pilgrim most of his life in order to find a land that God would use to eventually bring forth the Savior. The ultimate example is Jesus, who would not be turned from going to the cross in order to bring salvation. Stories like these are what we expect when God calls the prophet Jonah to take the message of salvation to the cruel Ninevites, but we could not be more wrong. Jonah is a book of surprises. For example, other books of the Old Testament have prophets speaking a word of judgment against the surrounding pagan nations; but Jonah actually travels to the judged nation. Often Old Testament prophets are revealed as less than perfect but are still seen as the noble messengers of God, but this isn't the case with Jonah. He is not shown in a favorable light. Moses and Jeremiah were reluctant and shrank back from their assignments, but Jonah isn't merely hesitant. He flatly refuses to go. Pagan sailors show more compassion for Jonah than he shows for the people of Nineveh. The people of Nineveh would soon experience the judgment of God on their city much like did the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah. You remember what happened. Jonah is saved from drowning by being swallowed by a great fish. He travels submarine style back to where he was supposed to be. Yet, this cranky prophet is used by God to bring the greatest revival recorded in Scripture to some of the most hardened sinners in Scripture. What is the point of the book of Jonah? Why did God include it in the Bible? The story of Jonah was written to Jews who had returned from exile in Babylon. The people that surrounded them saw them as enemies. It must have been easy to believe the whole world hated them and, therefore, they felt justified to hate the whole world. The natural reaction would be to entrench their group to protect themselves. The book of Jonah challenges God's people to rise above their hatred of others, and see the world through the eyes of their Creator God. The only thing that equals God's power to churn the seas is His love for His creation. God hates nothing He has made. He yearns to restore it to Himself. In difficult times, it is easy to be impacted by our circumstances, our own prejudices, our own likes and dislikes—all influenced by past experiences, historical, tribalistic fears, or even hatred. As we consider someone across the border, or in a neighboring village or city, or someone who practices a different religious practice, or maybe even someone who is hostile to the Christian faith, we must recognize that God loves and cares about EVERYONE. So, why do WE care about two billion people who live and die and have never even heard the name of Jesus? The simple answer is because God cares about them. Because His Spirit lives in us, we share His passion to reach the nations. Be encouraged today. God has put each of us in the specific place, among the specific people, with the resources He wants us to use, IN HIS POWER AND STRENGTH to rise above our own circumstances and prejudices to see everyone through the eyes of the Creator God, and to share with them the transforming message of Jesus Christ. I pray God’s richest blessing and provision for each of you as you serve Him faithfully and as you encourage each other. David Neely Co-founder The Unfinished Task Network  The presentation was interesting enough on its own merits, but I sat up and took notice of one particular statement. I was participating in a think tank gathered for the purpose of considering how best to move forward with development among refugee communities in light of past experience and predicted future trends. Our presenter reminded us of the minimum guidelines and accountability outlined and described in “The Sphere Project”, then moved on to consider specific humanitarian contexts. He provided personal examples, including his involvement in responding to the Syrian Refugee crisis. It was the moment he shared their vision statement from that response that gripped me and continues to hold my imagination captive. According to our speaker, they had been guided by this simple yet profound mandate: “Dignity Now; Hope for Eternity.” I cannot conceive of a clearer description or mandate for what we hope to achieve in holistic church planting—restore dignity now, and instill hope for eternity through establishing prophetic communities of faith that embody the transforming Gospel of Jesus Christ.

Dane Fowlkes, Ph.D. The Nature of Man’s Greatest Need

“Too often in church planting we have relegated God’s transforming work to spiritual realities and assigned earthly matters to science and technology. The result is a schizophrenic Christianity that leaves everyday problems of human life to secular specialists and limits God to matters of eternity. A truly holistic approach to mission rooted in biblical truth is as essential in planting vital churches that remain Christ-centered over the generations as it is in Christian ministries of compassion” (Paul G. Hiebert, Foreword to Bryant L. Myers’ Walking With the Poor: Principles and Practices of Transformational Development, 2011). The idea of transformational development wedded to Christian witness is not a new concept. Myers sets forth clearly the idea of transformational development in his seminal work, Walking With the Poor: Principles and Practices of Transformational Development (Orbis Books, 2011). His use of the term reflects a deep seated conviction that what we are to be about in entering people groups and communities is seeking change “in the whole of human life materially, socially, psychologically and spiritually.” Myers goes on to say that Christian witness is concerned with communicating that “God has, through his Son, made it possible for every human being to be in a covenant relationship with God.” Myers chooses to use the term “Christian witness” over against “evangelism” because evangelism for him conjures up images of street evangelists broadcasting monologues loudly through megaphones, or crusade evangelists preaching passionately and persuasively to stadiums filled with people. Instead, he sees Christian witness as proclaiming the gospel by “life, word, and deed.” This brings us to what holistic mission is all about: restoration of relationships. “God’s inherent nature is good. One of the ways this is shown in the Bible is through the central theme of justice and care for the poor in scripture. Consequently, poverty and oppression are symptoms of something fundamentally wrong in the relationship between God and humanity. The biblical narrative describes an arc of history starting from a life of wholeness in creation (Genesis 1 and 2) that was marred by the Fall (Genesis 3). The consequence was broken relationships—ultimately with God, but also with each other, with ourselves and with the whole of creation.” (Tearfund: “Understanding Poverty: Restoring Broken Relationships”) A holistic approach to church planting seeks to restore peoples to proper and right relationships with God, with each other, themselves and the world on which they depend. “Poverty itself can be understood as a state caused by broken relationships—a broken relationship with God that causes us to be separated from Him and act contrary to His desire for our lives; a broken relationship with each other that causes us to ignore God’s desire for us to love one-another as we love ourselves; a broken understanding of ourselves, forgetting that we are made in God’s image, causing us to ignore God’s ways and be hard-hearted; and a broken relationship with the world in which we live, abusing the resources we are to be stewards of and with which we have been entrusted” (Stephen Gaukroger, Clarion Trust International). Holistic church planting engages unreached people at their point of greatest need, namely the restoration of broken relationships:

Holistic or Integral Mission insists that our faith requires action in terms of the way we live and conduct our relationships. It demands we take seriously Christ’s admonition to love both God and our neighbor. According to Jesus, the motivation behind the messages of the Old Testament Prophets is based on this principle of reciprocating Love. Holistic mission is nothing less than transformation resulting from all-consuming love for Christ and for those whom He has created in the imago dei. “Poverty is the result of a social and structural legacy of broken relationships with God, a distorted understanding of self, unjust relationships between people, and exploitive relationships with the environment. These broken relationships not only affect individuals’ lives, decisions and actions, but also create broken systems, leading to problems such as power imbalances and corrupt governments. These fractures are made worse by conflicts and natural disasters, many of which also have roots in the broken relationships between God, humanity, and wider creation” (Anna Ling and Hannah Swithinbank, Tearfund). The Role of Local Churches in Community Transformation “The church occupies a distinct space in communities, nations and the world. It is privileged in its reach at all levels, connecting at the level of the individual right up to international organizations. This creates huge potential for its role in tackling poverty, in all its forms, across the globe” (Lucie Wooley, “Integral, Inspirational and Influential: The role of local churches in humanitarian and development responses,” Tearfund: 2017). Christians are called to take intentional and strategic initiative in restoring broken relationships. Integral mission “understands that God is working to restore broken relationships by responding holistically to people’s needs, including economic, emotional, spiritual and physical ones. The church, as the body of Christ, therefore has a distinctive role to play in fulfilling this mission” (Ling and Swithinbank, “Understanding Poverty: Restoring Broken Relationships,” Tearfund: 2019). Churches are by definition prophetic communities of faith (please see our earlier blog: “The ‘Why’ of Holistic Church Planting, Part 1”, 12/2/19). The response of The Unfinished Task Network is to mobilize the planting of churches that are by nature and effect agents of spiritual and community transformation. The aim of transformational church planting is to restore all four different types of broken relationship. This approach goes beyond meeting basic needs, equipping churches to enable and empower people to flourish as they come to know Christ individually and become agents of transformed relationships:

Dane Fowlkes, Ph.D. Co-Founder, The Unfinished Task Network  Everything I have done since I entered vocational Christian ministry at the age of 20 has related to the work of local churches—pastor, missionary, theological educator, college professor, and international relief worker. I love the Church, and have sought to plant and strengthen local expressions on four continents. The most common visible expression of Christianity is the local church, but many are hard-pressed to define her. What is “church?” Offered automatically without thinking but with an ‘everyone knows that’ expression, many people define church as “a body of baptized believers.” But what does that mean? That so-called definition speaks more to what qualifies you to be a member of a church than it offers anything about what a church is. Tragically, some pour themselves into planting churches with only a vague understanding of what it means to be and do church. Fortunately for all of us, Scripture speaks to the nature of the church in descriptive fashion. Consider Acts 2:42-47; 4:32-37. The Book of Acts is our one book of history in the New Testament and gives us our clearest snapshot of what life was like in the earliest churches. As we read Acts, we are careful not to take any single description and make it prescriptive, but if we see the same description repeated, we may have great confidence in drawing some conclusions/principles that we can apply today. The description of the earliest church in Acts 2 and 4 help us redefine the meaning of church. More than describing what churches do, we actually see what a church is. From what we read in the Book of Acts over against the backdrop of the Old Testament, we can say that a church is a prophetic community of faith. While some may disregard this as a minimalist definition, each simple word holds profound meaning and is determinative in our approach to church planting. 1. PROPHETIC (vv., 43, 47) “Everyone was filled with awe, and many wonders and miraculous signs were done by the apostles.” (v. 43) “praising God and enjoying the favor of all the people. And the Lord added to their number daily those who were being saved.” (v.47) Even a cursory consideration of these verses will, at the very least, cause the reader to stumble upon the incredible impact this earliest church had on both those who were a part of the fellowship and those who were yet to be a part. Using deeply grounded biblical terminology, this may best be termed “prophetic” ministry. Widespread misunderstanding prevails concerning the biblical concept of prophecy and prophetic ministry. The Old Testament prophets were not primarily men and women who predicted the future; they were individuals who received a word from the Lord and proclaimed it with such boldness and relevance that people responded—sometimes responded in repentance; at other times they responded in anger and hostility, to the point of harming the prophet himself. But no one remained unaffected and apathetic when a prophet spoke. The first element of being church is being prophetic—an agent of transformation in an unbelieving community, as well as within the believing community. Truly being “church” brings about transformation. A church without effect, isn’t really church. 2.. COMMUNITY (vv. 42, 44, 45). “They devoted themselves to… the fellowship, to the breaking of bread and to prayer.” (v. 42) “All the believers were together and had everything in common. Selling their possessions and goods, they gave to anyone as he had need. Every day they continued to meet together in the temple courts. They broke bread in their homes and ate together with glad and sincere hearts.” (vv. 44-45). That’s community! There is a terrible misnomer today. People say they “attend church,” but if Acts is giving us an accurate portrayal of church, you cannot attend church, you can only be church! Church is not a place where strangers assemble to attend and enjoy a program; church is a living organism in which strangers become family, and family deals with the worst and brings out the best in each of us.

“The more genuine and the deeper our community becomes, the more will everything else between us recede, the more clearly and purely will Jesus Christ and his work become the one and only thing that is vital between us. We have one another only through Christ, but through Christ we do have one another, wholly, and for all eternity.” (Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Life Together)

3. FAITH (vv. 42a). “They devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching.” (v. 42a) What were the apostles teaching? They were teaching Christ! They were reciting what they had heard and witnessed with their own eyes. They were describing their relationship with the Master. The early church was radically Christ-centered, and the result was radical discipleship. Relationship is everything. That means that discipleship is the expression of transformation within the believing community. This relationship with Jesus Christ is a radical one. Take a moment to read again for yourself what Jesus says about following him (Mt 10:34-39). Theology does matter. For proof, one need look no further than the historical schism between evangelism and the so-called “social gospel.” The ebb-and-flow of this ongoing debate has infected church planting strategy and methodology. The remedy for this infection is a return to a biblical understanding of church. The “why” of holistic church planting is rooted in our understanding of “church.” When we redefine church and understand it as a prophetic community of faith, we are compelled to establish churches that are agents of transformation, both within the believing community and in addressing the needs of the surrounding context. Dane Fowlkes, Ph.D. Co-Founder, The Unfinished Task Network  Peter and I sat together near the dining hall table, encompassed on either side by other former students of mine. The fellowship during the evening meal was an extension of the special reunion that had started only two hours earlier. I traveled back to Kenya for the purpose of reconnecting with students I had taught twenty years before as dean of a theological seminary situated high among the tea fields of Limuru. Peter is an exceptional and insightful Maasai who graduated with a Diploma in Theology and went on to earn advanced theological degrees. He is a leader among his village elders. As we laughed while enjoying reminiscing over a traditional meal, conversation shifted to my purpose for returning after all these years. Peter asked probing questions related to the subject at hand, which was what must be done to finish the task of reaching the unreached peoples of East Africa. He pressed the issue and stated that from his perspective, the churches that have been planted in Maasai land are seen by many in the villages as irrelevant. Peter explained that many villagers see the church as a Sunday place of worship and preaching, but when they have a need during the week they turn to either the government or NGOs (non government organization) to meet their needs. For all practical purposes, the church is irrelevant to the average villager, particularly during a time of great need or crisis. Peter asked the question that my colleagues and I had journeyed so far to address: What would happen if the churches we plant among the least reached could be seen as centers of community development? Peter’s question is a vital one to be asked of every indigenous church plant, especially those started in areas of gripping need. What would happen if the church is seen as the center of community development? What changes when the church becomes the primary source of help for a village or community in symphony with government and non-government resources? What if addressing need is not merely a gateway to evangelism, but the embodiment of what the church is meant to be? One undeniable result of a paradigm shift toward holistic mission is that the church is seen as relevant to all of Village life, and that changes everything. Our goal is not to plant churches that are culturally relevant; our goal is to live out the holistic mission of Christ to enjoy an all-consuming love for God, and to express corresponding self-sacrificing love for our neighbors in every village and city. Relevance follows identification. When we actively identify with the compassionate person of Christ who healed individuals and grieved over estranged people groups, the result is undeniable relevance of the church of our Lord Jesus Christ. Holistic mission produces a relevant church. Dane Fowlkes, Ph.D. Co-Founder, The Unfinished Task Network  My colleagues and I of The Unfinished Task Network were recently privileged to meet with pastors in East Africa for the purpose of considering the Unfinished Task before us. This was no random gathering of African pastors. Instead, these still identify themselves as members of Class 510, a cohort that started and completed together the Diploma of Theology degree at Kenya Baptist Theological College back in November of 1999. The final course that I taught them in 1998 was an elective entitled “The Unfinished Task,” in which I challenged the students of Class 510 to move from being beneficiaries of mission to serving as agents of mission. David Neely, a fellow instructor at KBTC, and I dreamed of and prayed for students to catch a vision for indigenous church planting among the least reached people groups of East Africa. We considered biblically and strategically what would be required of our students to enter into missionary endeavor themselves, rather than depending on Western missionaries as had been the case for well over one hundred years in Kenya. The challenge was met at first with incredulity—was it even acceptable to the Baptist mission to speak in these terms? One by one, the students recognized the aberrant gap, and embraced the calling themselves to go and send rather than continue waiting and receiving. As the course came to a close, the twenty three students of Class 510 presented me with a wooden carving of the nation of Kenya to which they attached a small notepad containing the name of each student and the unreached people group they were committing to engage with the Gospel. Fast forward twenty years. Under what I understood to be the prompting of God’s Spirit, I was compelled to gather these students again from all across East Africa and ask them to share their story—what God has done in and through them over these many years since we last discussed and agonized over the unreached peoples of East Africa, and the gut wrenching absence of indigenous missionaries among them. I reached out to my former missionary colleague and another close friend, and we began working to bring Class 510 back together. Members of the class accepted our invitation, and sixteen of the original twenty three came together in Tigoni, Kenya, most of whom had enjoyed very little communication among themselves during the previous twenty years. Five members of the original group had gone on to be with the Lord, so the sixteen members of Class 510 that gathered represented 89% of the students still living. What we learned as they shared their story was nothing short of awe inspiring. These twenty-three servants of Christ had engaged 29 language groups with the Gospel—6 of which are considered unreached people groups. They had planted 275 churches, that in turn had planted another 96 churches. They accomplished all this without the aid of Western missionaries and funding, and in the face of enormous challenges, intense loneliness, and heart-rending suffering. They acknowledged their short comings, and admitted the discouragement they had endured along the way. Despite setbacks and occasional losses that would have turned back most Christian leaders, they remain faithful to finishing the task of reaching the least reached around them. At the close of our Class 510 reunion, we challenged and recommissioned them to go out with a renewed vision for indigenous church planting among the least reached peoples of East Africa. Only time and eternity will reveal the full extent of their sacrifice, but based on historical and empirical evidence, we have every reason to believe that theirs will be an exponential impact for the gospel and glory of Christ among the nations. Dane Fowlkes, Ph.D. Co-Founder, The Unfinished Task Network dr. stan wafler phdStan and his wife, Pam, lived in Arua, Uganda, from 2001-2015. They served in a variety disciple-making roles, including Bible translation consulting, orality training, pastor training, marriage encouragement ministry, expository preaching training, and student ministry.

As I share this final selection from the article, I want to point you to a host of resources found on the website of the International Orality Network https://orality.net/. You can find journals, training, conferences, and connect with others who are on the journey with you to engage with the oral cultures of the world. Orality opens windows of understanding to deep cultural values. I never ceased to be amazed at the creativity and expression of a small group of people working together on a drama. The Ugandans we knew seemed to be set free to enter the story fully when they were developing a drama. After a drama the group would learn new truths because they had lived the story. We gained some wonderful insights about culture from seeing Ugandans act dramas of Bible stories and then debrief together. We saw the proper way to treat visitors displayed in the drama about Abraham entertaining three visitors. In that brief drama we saw honor and hospitality vividly displayed. This indirect kind of learning gave us rich cultural insight about many topics. The use of drama helped us understand how to interpret the ways we were treated as guests in the village and ways we could show honor to visitors in our home. Orality helps highlight the uniqueness and beauty of the local language. The process of crafting oral Bible stories with a group of nationals enhanced my appreciation of the beauty and uniqueness of the Lugbara language. During this process I learned about the tonal richness of the language and the uniqueness of the vocabulary within the eight dialects. These were treasured experiences which would not have been part of my journey into Lugbara culture apart my involvement with nationals in the oral story crafting process. For example, I learned that in Genesis 4:7 the written text of the Lugbara Bible said that “sin is crouching at your door” but this is a meaningless metaphor in the Lugbara language. After unpacking this metaphor, story crafters re-expressed this metaphor as “sin is near you and about to catch you.” This is a very serious warning that you might use if someone is about to step on a snake. When hearing the vocabulary about God’s covenant with Abraham I gained a new insight into relational terminology. In Genesis 15:18, God made a covenant with Abraham which is translated in Lugbara as “God joined mouth with Abraham.” This beautiful picture of face to face communication lays the foundation for the new covenant relationship provided through Jesus. I never would have known the words kici kici even by reading 1 Kings 18:38 in Lugbara which describes the fire that fell on the altar built by Elijah. When I heard the oral story in Lugbara and observed silence of the listeners, I knew the expression kici kici brought a unique expression of the dramatic and complete destruction of the stone altar, the wood, the bull and the water in the trench. The dramatic pause of the storyteller and the sound of kici kici captured the wonder of what God had done very differently than the words that were written on the page of the Bible. These examples illustrate that the oral expression is dynamic and colorful and will often be missed in a process that seeks to use only a literate process or read words on a printed page. Orality encourages clarification. Another benefit of using oral methods is the methodology of questions and discussion. At first we did not realize how rare it was for individuals to be afforded the opportunity to ask questions about spiritual issues. There was a strong tradition of top-down authority based teaching in the established churches. In some churches people were told that it that was sinful to ask questions. The expectation of the church leadership was that people should come and listen quietly without asking questions. We often encountered people who carried lots of confusion about the Bible but were told that asking questions was not an appropriate response to the Bible. We never had much influence with the church leaders on this point. We chose not to publicly oppose church leaders or challenge their authority. However, we did train as many people as we could to use oral Bible studies, questions, dramas and debriefing. This new interactive paradigm for discovering truth from the Bible created opportunities for new disciples to grow in their knowledge of the Word of God and train others. Orality is more than a tool for packaging the message of the Gospel. Orality offers opportunities and tools for the beginning missionary even during the early days of language and culture learning for building relationships that allow you to learn the worldview of your target audience. As I back on our years in Uganda, what we learned about our people was just as important as learning how to communicate the message to them. I can see that we had many weaknesses and we made mistakes along the way. When it was time to depart Uganda the people said many wonderful things to us. Nobody actually thanked me for a specific Bible study, sermon or training I had taught. However, several people said they were thankful for us because they knew that we loved them. I will never forget those words, “we know you love us because you learned our language, you ate our food, you slept on the ground with us and you walked on the road with us.” I am very thankful for the trainers and mentors who introduced me to orality and mentored me in language and culture learning along the way. I have no regrets for the efforts I made to leave my comfortable, literate, expositional world and begin the journey of understanding another way of learning and communicating. I am richer because of this journey. dr. stan wafler phdStan and his wife, Pam, lived in Arua, Uganda, from 2001-2015. They served in a variety disciple-making roles, including Bible translation consulting, orality training, pastor training, marriage encouragement ministry, expository preaching training, and student ministry.

In this third selection, I want to share two more examples of using oral methods to gain advantages for language and culture learning. Orality assists with contextualization. Orality helped Ugandans see that the Bible is the primary authority for truth based transformation. Rather than the missionary being the expert or authority at the center of the group, the Bible story became the center for the group. Orality allows a transfer of authority away from an expert or outsider and puts the focus of authority on God’s Word. This is a key factor in helping nationals deal with worldview transformation issues where traditional culture clashes with the Bible. Traditionally, even among Christians there had been resistance to the truth that both men and women were made in God’s image. When a story crafting group tried to unpack this term they struggled to see how the image of God was a relevant truth with respect to male-female relationships, inter-tribal relations, and marriage. The nationals were wary to accept the Western view that they had been told. Of course they are aware of the agenda of the Western world to challenge the traditional roles of men and women. The image of God (Genesis 1:27) was translated literally as image or likeness in the Bible that was readily available in the local language. However, after more discussion about the uniqueness of human beings in God’s creation, the story crafting group expressed a more functional meaning as personality or character. God has given to human beings alone the unique ability to speak, think, choose, and have relationship with God. The process of unpacking biblical terms and re-expressing them allowed the group to discover a more biblical understanding to a culturally charged topic. Orality elevates local knowledge and expertise. I enjoyed (on most days) learning a new skill and the language that went along with that skill. Unfortunately Ugandans were more familiar with being taken for granted in their relationships with Westerners. Due to the lingering influence of colonialism, an unwritten script seemed to cast the Westerner as the expert in most every situation. Although this was the overt cultural protocol, this script was not relevant or helpful for building relationships with mutual appreciation. In order to overcome this well-established barrier we needed to operate off of a new script. One way we learned to do this was to ask a Ugandan to teach us a skill in the way they would teach a child. Some examples were: “Teach me the process of growing and processing coffee.” We discovered that in oral societies, important skills are passed on through oral learning processes. The oral learning processes involved listening, watching, modeling, receiving instruction, and correction. We learned as we picked coffee beans, dried them in the sun, removed the cover from them and eventually roasted them together. On another day, a colleague and I asked, “Can you teach us how to make flour?” We learned like children to pick up the cassava and place it in a large wooden mortar made from a hollow log. Actually, there were children who sat down to enjoy watching the mundus (Westerners) learn tasks that they had already mastered. We handled the large heavy wooden pestle, which was about five feet long and three inches in diameter. Quickly we learned that we did not have the skill, the muscles, or the rhythm of the lady who taught us. She would let us hold the pestle as she pounded so we could feel the rhythm and the force needed to pound cassava into powder. We would then try on our own and become the laughingstock of our teacher and her children. Accepting the position of humility and learning a skill from an oral learner set us apart from other Westerners. Of course, we learned new vocabulary during the process but more importantly we made friends because we asked nationals to excel at an oral learning process. Dr. stan wafler phdStan and his wife, Pam, lived in Arua, Uganda, from 2001-2015. They served in a variety disciple-making roles, including Bible translation consulting, orality training, pastor training, marriage encouragement ministry, expository preaching training, and student ministry.

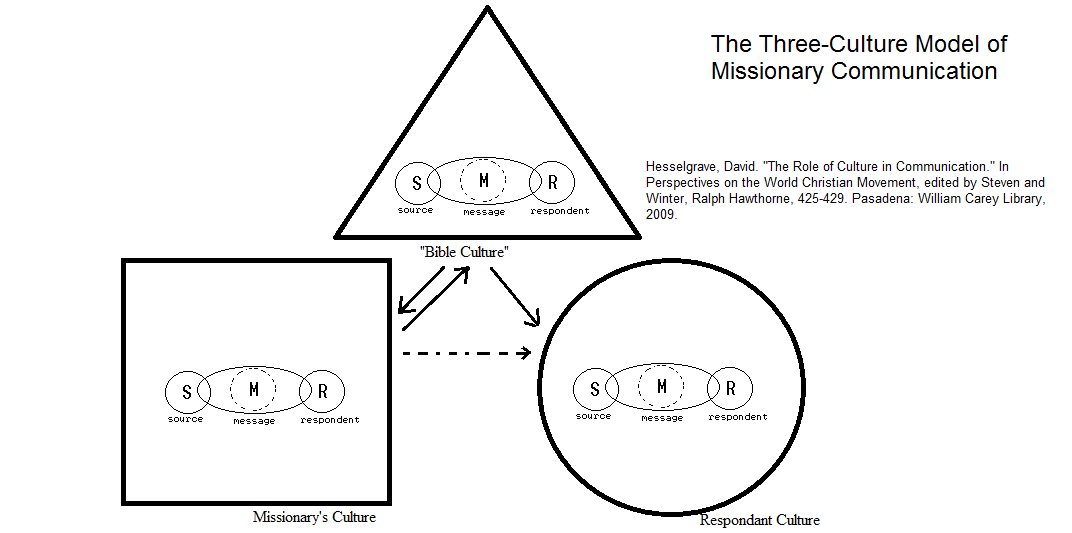

Now I want to share some helpful models of cross cultural communication and some of their practical applications. Let’s consider the challenge of missionary communication in light of some observations from communication theory. Charles Kraft wrote approvingly of this statement about “Where is meaning found?” in communication.1 “Meanings are in people, [They are] covert responses contained in the human organism. Meanings are personal, our own property. We learn meanings, we add to them, we distort them, forget them, change them. We cannot find them. They are in us, not in messages. Communication does not consist of the transmission of meaning. Meanings are not transmittable, and meanings are not in the message, they are in the message users.”2 With this communication challenge in mind we must not forget that we do not bring meaning with us but rather we are transmitters of a message. We begin from our own culture with a source and formulate a message with a target audience in mind. We interact with Scripture that is also a reflection of a source, a message and a multitude of target audiences. Our listeners in our target audience will hear the message and formulate meaning based on their worldview. Hesselgrave developed the diagram of the three-culture model of missionary communication. Awareness of orality and oral methodologies helped me stay aware and engaged in these three cultures for learning culture and language. I never felt like I had fully uncovered the meanings in the people to whom I was delivering the message. Indeed, people are like onions and their layers come off slowly. There was never an end to language and culture learning but the process was valuable because of the discoveries about the meanings in people along the way. My observation has been that as outsiders coming into a community new to us we tend to often highly value the message we bring but we fail to give the same value to the meaning inside our target audience. Instead we tend to focus on improving our content rather than uncovering the layers of meaning in our target culture. Oral methodologies offer advantages and opportunities to make progress on these two fronts simultaneously. Orality allows outsiders legitimate opportunities to be learners alongside nationals. We desire to see those in our target culture transformed by the Gospel but we will never know the knowledge they already possess, what they have actually understood, or the worldview that shapes their understanding until we stop talking and start listening. Oral methods allow significant time for listening and observing. I have seen missionaries miss the opportunity to be learners. One missionary asked me why I was wasting so much time with learning the local language. He believed that I was slowing down the volume of content that could be delivered if I would simply lecture in English. With that kind of “data dump” understanding of communication, we might as well record ourselves and then increase the playback speed of the “data dump.” Oral methods acknowledge the significance of learning from nationals and with nationals rather than merely coming to unload knowledge upon them. When a small group retold, dramatized, and discussed a story from the Bible, everyone had the opportunity to become a learner. My presence as a missionary did not cast me in the role of the expert because others in the group were far beyond me in language and storytelling skills. During the storying process, I learned new truths in the story previously overlooked because of my own cultural blindness. As a group member, I learned from the story and learned from and with nationals. Learning together created valuable relational bonds. Orality is participatory. I learned that Ugandans (like most people) enjoyed participation in activities where they excel. I spent lots of time sitting under trees in a circle listening to them process stories in their local language. The people that I worked with most closely with were not illiterates but had various levels of education and reading ability in the local language and in English. As I listened and learned the local language along the way, they allowed me to participate by asking questions and growing in my own contribution as a group member. A lead story crafter would read and listen to a recorded story and draft an oral version. This was necessary because the available translation of the Bible had a good number of foreign words, obscurities, and ambiguities. As the oral drafting continued week after week, the group discovered numerous previously misunderstood figures of speech. At that point, I became a helpful resource person in the group. After understanding the meaning of the biblical metaphor, the group would then translate that metaphor accurately, clearly, and naturally. The group would then own the new oral story and they were eager to share it with their own families and neighbors. 1 Charles Kraft, Communication Theory for Christian Witness (Abingdon: Nashville, 1960), 112-13 is referenced by David Hesselgrave, Communicating Christ Cross-Culturally 2nd Edition (Zondervan: Grand Rapids, MI, 1991) 63. 2 David K. Berlo, The Process of Communication: An Introduction to Theory and Practice (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1960) 7-10. |

Archives

October 2020

Categories |

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed