Dr. stan wafler phdStan and his wife, Pam, lived in Arua, Uganda, from 2001-2015. They served in a variety disciple-making roles, including Bible translation consulting, orality training, pastor training, marriage encouragement ministry, expository preaching training, and student ministry.

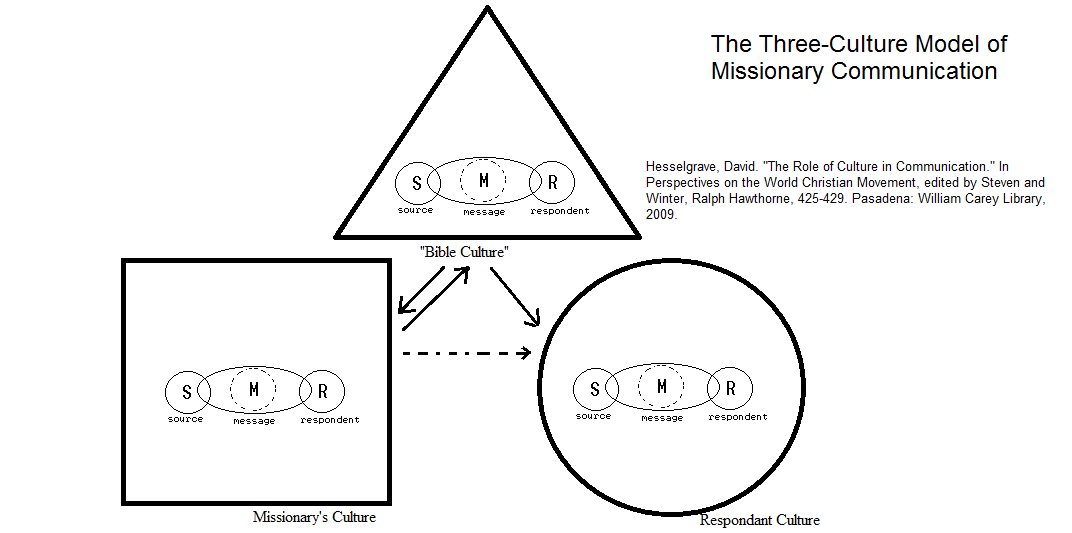

Now I want to share some helpful models of cross cultural communication and some of their practical applications. Let’s consider the challenge of missionary communication in light of some observations from communication theory. Charles Kraft wrote approvingly of this statement about “Where is meaning found?” in communication.1 “Meanings are in people, [They are] covert responses contained in the human organism. Meanings are personal, our own property. We learn meanings, we add to them, we distort them, forget them, change them. We cannot find them. They are in us, not in messages. Communication does not consist of the transmission of meaning. Meanings are not transmittable, and meanings are not in the message, they are in the message users.”2 With this communication challenge in mind we must not forget that we do not bring meaning with us but rather we are transmitters of a message. We begin from our own culture with a source and formulate a message with a target audience in mind. We interact with Scripture that is also a reflection of a source, a message and a multitude of target audiences. Our listeners in our target audience will hear the message and formulate meaning based on their worldview. Hesselgrave developed the diagram of the three-culture model of missionary communication. Awareness of orality and oral methodologies helped me stay aware and engaged in these three cultures for learning culture and language. I never felt like I had fully uncovered the meanings in the people to whom I was delivering the message. Indeed, people are like onions and their layers come off slowly. There was never an end to language and culture learning but the process was valuable because of the discoveries about the meanings in people along the way. My observation has been that as outsiders coming into a community new to us we tend to often highly value the message we bring but we fail to give the same value to the meaning inside our target audience. Instead we tend to focus on improving our content rather than uncovering the layers of meaning in our target culture. Oral methodologies offer advantages and opportunities to make progress on these two fronts simultaneously. Orality allows outsiders legitimate opportunities to be learners alongside nationals. We desire to see those in our target culture transformed by the Gospel but we will never know the knowledge they already possess, what they have actually understood, or the worldview that shapes their understanding until we stop talking and start listening. Oral methods allow significant time for listening and observing. I have seen missionaries miss the opportunity to be learners. One missionary asked me why I was wasting so much time with learning the local language. He believed that I was slowing down the volume of content that could be delivered if I would simply lecture in English. With that kind of “data dump” understanding of communication, we might as well record ourselves and then increase the playback speed of the “data dump.” Oral methods acknowledge the significance of learning from nationals and with nationals rather than merely coming to unload knowledge upon them. When a small group retold, dramatized, and discussed a story from the Bible, everyone had the opportunity to become a learner. My presence as a missionary did not cast me in the role of the expert because others in the group were far beyond me in language and storytelling skills. During the storying process, I learned new truths in the story previously overlooked because of my own cultural blindness. As a group member, I learned from the story and learned from and with nationals. Learning together created valuable relational bonds. Orality is participatory. I learned that Ugandans (like most people) enjoyed participation in activities where they excel. I spent lots of time sitting under trees in a circle listening to them process stories in their local language. The people that I worked with most closely with were not illiterates but had various levels of education and reading ability in the local language and in English. As I listened and learned the local language along the way, they allowed me to participate by asking questions and growing in my own contribution as a group member. A lead story crafter would read and listen to a recorded story and draft an oral version. This was necessary because the available translation of the Bible had a good number of foreign words, obscurities, and ambiguities. As the oral drafting continued week after week, the group discovered numerous previously misunderstood figures of speech. At that point, I became a helpful resource person in the group. After understanding the meaning of the biblical metaphor, the group would then translate that metaphor accurately, clearly, and naturally. The group would then own the new oral story and they were eager to share it with their own families and neighbors. 1 Charles Kraft, Communication Theory for Christian Witness (Abingdon: Nashville, 1960), 112-13 is referenced by David Hesselgrave, Communicating Christ Cross-Culturally 2nd Edition (Zondervan: Grand Rapids, MI, 1991) 63. 2 David K. Berlo, The Process of Communication: An Introduction to Theory and Practice (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1960) 7-10.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

October 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed