dr. stan wafler phdStan and his wife, Pam, lived in Arua, Uganda, from 2001-2015. They served in a variety disciple-making roles, including Bible translation consulting, orality training, pastor training, marriage encouragement ministry, expository preaching training, and student ministry.

As I share this final selection from the article, I want to point you to a host of resources found on the website of the International Orality Network https://orality.net/. You can find journals, training, conferences, and connect with others who are on the journey with you to engage with the oral cultures of the world. Orality opens windows of understanding to deep cultural values. I never ceased to be amazed at the creativity and expression of a small group of people working together on a drama. The Ugandans we knew seemed to be set free to enter the story fully when they were developing a drama. After a drama the group would learn new truths because they had lived the story. We gained some wonderful insights about culture from seeing Ugandans act dramas of Bible stories and then debrief together. We saw the proper way to treat visitors displayed in the drama about Abraham entertaining three visitors. In that brief drama we saw honor and hospitality vividly displayed. This indirect kind of learning gave us rich cultural insight about many topics. The use of drama helped us understand how to interpret the ways we were treated as guests in the village and ways we could show honor to visitors in our home. Orality helps highlight the uniqueness and beauty of the local language. The process of crafting oral Bible stories with a group of nationals enhanced my appreciation of the beauty and uniqueness of the Lugbara language. During this process I learned about the tonal richness of the language and the uniqueness of the vocabulary within the eight dialects. These were treasured experiences which would not have been part of my journey into Lugbara culture apart my involvement with nationals in the oral story crafting process. For example, I learned that in Genesis 4:7 the written text of the Lugbara Bible said that “sin is crouching at your door” but this is a meaningless metaphor in the Lugbara language. After unpacking this metaphor, story crafters re-expressed this metaphor as “sin is near you and about to catch you.” This is a very serious warning that you might use if someone is about to step on a snake. When hearing the vocabulary about God’s covenant with Abraham I gained a new insight into relational terminology. In Genesis 15:18, God made a covenant with Abraham which is translated in Lugbara as “God joined mouth with Abraham.” This beautiful picture of face to face communication lays the foundation for the new covenant relationship provided through Jesus. I never would have known the words kici kici even by reading 1 Kings 18:38 in Lugbara which describes the fire that fell on the altar built by Elijah. When I heard the oral story in Lugbara and observed silence of the listeners, I knew the expression kici kici brought a unique expression of the dramatic and complete destruction of the stone altar, the wood, the bull and the water in the trench. The dramatic pause of the storyteller and the sound of kici kici captured the wonder of what God had done very differently than the words that were written on the page of the Bible. These examples illustrate that the oral expression is dynamic and colorful and will often be missed in a process that seeks to use only a literate process or read words on a printed page. Orality encourages clarification. Another benefit of using oral methods is the methodology of questions and discussion. At first we did not realize how rare it was for individuals to be afforded the opportunity to ask questions about spiritual issues. There was a strong tradition of top-down authority based teaching in the established churches. In some churches people were told that it that was sinful to ask questions. The expectation of the church leadership was that people should come and listen quietly without asking questions. We often encountered people who carried lots of confusion about the Bible but were told that asking questions was not an appropriate response to the Bible. We never had much influence with the church leaders on this point. We chose not to publicly oppose church leaders or challenge their authority. However, we did train as many people as we could to use oral Bible studies, questions, dramas and debriefing. This new interactive paradigm for discovering truth from the Bible created opportunities for new disciples to grow in their knowledge of the Word of God and train others. Orality is more than a tool for packaging the message of the Gospel. Orality offers opportunities and tools for the beginning missionary even during the early days of language and culture learning for building relationships that allow you to learn the worldview of your target audience. As I back on our years in Uganda, what we learned about our people was just as important as learning how to communicate the message to them. I can see that we had many weaknesses and we made mistakes along the way. When it was time to depart Uganda the people said many wonderful things to us. Nobody actually thanked me for a specific Bible study, sermon or training I had taught. However, several people said they were thankful for us because they knew that we loved them. I will never forget those words, “we know you love us because you learned our language, you ate our food, you slept on the ground with us and you walked on the road with us.” I am very thankful for the trainers and mentors who introduced me to orality and mentored me in language and culture learning along the way. I have no regrets for the efforts I made to leave my comfortable, literate, expositional world and begin the journey of understanding another way of learning and communicating. I am richer because of this journey.

1 Comment

dr. stan wafler phdStan and his wife, Pam, lived in Arua, Uganda, from 2001-2015. They served in a variety disciple-making roles, including Bible translation consulting, orality training, pastor training, marriage encouragement ministry, expository preaching training, and student ministry.

In this third selection, I want to share two more examples of using oral methods to gain advantages for language and culture learning. Orality assists with contextualization. Orality helped Ugandans see that the Bible is the primary authority for truth based transformation. Rather than the missionary being the expert or authority at the center of the group, the Bible story became the center for the group. Orality allows a transfer of authority away from an expert or outsider and puts the focus of authority on God’s Word. This is a key factor in helping nationals deal with worldview transformation issues where traditional culture clashes with the Bible. Traditionally, even among Christians there had been resistance to the truth that both men and women were made in God’s image. When a story crafting group tried to unpack this term they struggled to see how the image of God was a relevant truth with respect to male-female relationships, inter-tribal relations, and marriage. The nationals were wary to accept the Western view that they had been told. Of course they are aware of the agenda of the Western world to challenge the traditional roles of men and women. The image of God (Genesis 1:27) was translated literally as image or likeness in the Bible that was readily available in the local language. However, after more discussion about the uniqueness of human beings in God’s creation, the story crafting group expressed a more functional meaning as personality or character. God has given to human beings alone the unique ability to speak, think, choose, and have relationship with God. The process of unpacking biblical terms and re-expressing them allowed the group to discover a more biblical understanding to a culturally charged topic. Orality elevates local knowledge and expertise. I enjoyed (on most days) learning a new skill and the language that went along with that skill. Unfortunately Ugandans were more familiar with being taken for granted in their relationships with Westerners. Due to the lingering influence of colonialism, an unwritten script seemed to cast the Westerner as the expert in most every situation. Although this was the overt cultural protocol, this script was not relevant or helpful for building relationships with mutual appreciation. In order to overcome this well-established barrier we needed to operate off of a new script. One way we learned to do this was to ask a Ugandan to teach us a skill in the way they would teach a child. Some examples were: “Teach me the process of growing and processing coffee.” We discovered that in oral societies, important skills are passed on through oral learning processes. The oral learning processes involved listening, watching, modeling, receiving instruction, and correction. We learned as we picked coffee beans, dried them in the sun, removed the cover from them and eventually roasted them together. On another day, a colleague and I asked, “Can you teach us how to make flour?” We learned like children to pick up the cassava and place it in a large wooden mortar made from a hollow log. Actually, there were children who sat down to enjoy watching the mundus (Westerners) learn tasks that they had already mastered. We handled the large heavy wooden pestle, which was about five feet long and three inches in diameter. Quickly we learned that we did not have the skill, the muscles, or the rhythm of the lady who taught us. She would let us hold the pestle as she pounded so we could feel the rhythm and the force needed to pound cassava into powder. We would then try on our own and become the laughingstock of our teacher and her children. Accepting the position of humility and learning a skill from an oral learner set us apart from other Westerners. Of course, we learned new vocabulary during the process but more importantly we made friends because we asked nationals to excel at an oral learning process. Dr. stan wafler phdStan and his wife, Pam, lived in Arua, Uganda, from 2001-2015. They served in a variety disciple-making roles, including Bible translation consulting, orality training, pastor training, marriage encouragement ministry, expository preaching training, and student ministry.

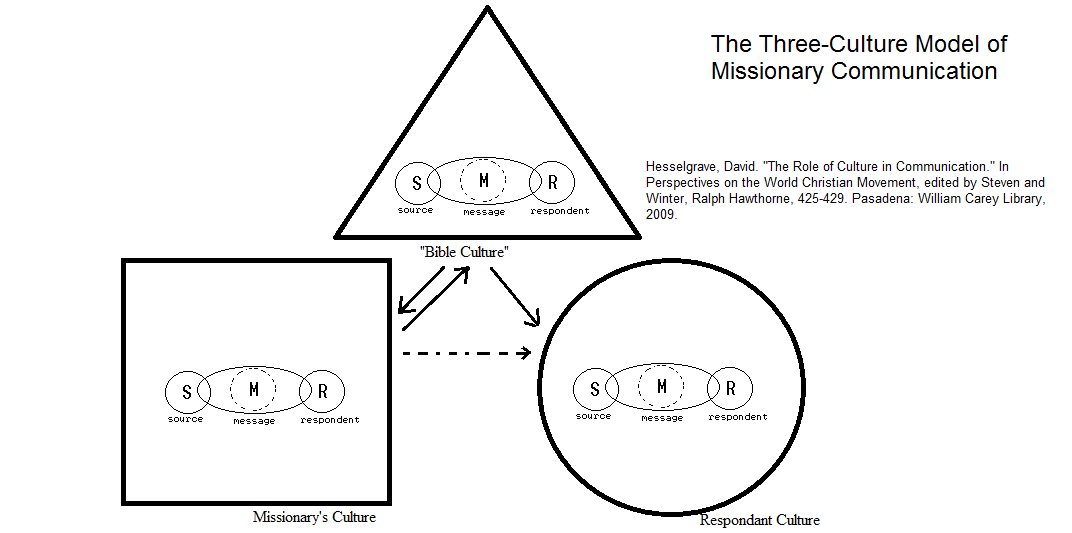

Now I want to share some helpful models of cross cultural communication and some of their practical applications. Let’s consider the challenge of missionary communication in light of some observations from communication theory. Charles Kraft wrote approvingly of this statement about “Where is meaning found?” in communication.1 “Meanings are in people, [They are] covert responses contained in the human organism. Meanings are personal, our own property. We learn meanings, we add to them, we distort them, forget them, change them. We cannot find them. They are in us, not in messages. Communication does not consist of the transmission of meaning. Meanings are not transmittable, and meanings are not in the message, they are in the message users.”2 With this communication challenge in mind we must not forget that we do not bring meaning with us but rather we are transmitters of a message. We begin from our own culture with a source and formulate a message with a target audience in mind. We interact with Scripture that is also a reflection of a source, a message and a multitude of target audiences. Our listeners in our target audience will hear the message and formulate meaning based on their worldview. Hesselgrave developed the diagram of the three-culture model of missionary communication. Awareness of orality and oral methodologies helped me stay aware and engaged in these three cultures for learning culture and language. I never felt like I had fully uncovered the meanings in the people to whom I was delivering the message. Indeed, people are like onions and their layers come off slowly. There was never an end to language and culture learning but the process was valuable because of the discoveries about the meanings in people along the way. My observation has been that as outsiders coming into a community new to us we tend to often highly value the message we bring but we fail to give the same value to the meaning inside our target audience. Instead we tend to focus on improving our content rather than uncovering the layers of meaning in our target culture. Oral methodologies offer advantages and opportunities to make progress on these two fronts simultaneously. Orality allows outsiders legitimate opportunities to be learners alongside nationals. We desire to see those in our target culture transformed by the Gospel but we will never know the knowledge they already possess, what they have actually understood, or the worldview that shapes their understanding until we stop talking and start listening. Oral methods allow significant time for listening and observing. I have seen missionaries miss the opportunity to be learners. One missionary asked me why I was wasting so much time with learning the local language. He believed that I was slowing down the volume of content that could be delivered if I would simply lecture in English. With that kind of “data dump” understanding of communication, we might as well record ourselves and then increase the playback speed of the “data dump.” Oral methods acknowledge the significance of learning from nationals and with nationals rather than merely coming to unload knowledge upon them. When a small group retold, dramatized, and discussed a story from the Bible, everyone had the opportunity to become a learner. My presence as a missionary did not cast me in the role of the expert because others in the group were far beyond me in language and storytelling skills. During the storying process, I learned new truths in the story previously overlooked because of my own cultural blindness. As a group member, I learned from the story and learned from and with nationals. Learning together created valuable relational bonds. Orality is participatory. I learned that Ugandans (like most people) enjoyed participation in activities where they excel. I spent lots of time sitting under trees in a circle listening to them process stories in their local language. The people that I worked with most closely with were not illiterates but had various levels of education and reading ability in the local language and in English. As I listened and learned the local language along the way, they allowed me to participate by asking questions and growing in my own contribution as a group member. A lead story crafter would read and listen to a recorded story and draft an oral version. This was necessary because the available translation of the Bible had a good number of foreign words, obscurities, and ambiguities. As the oral drafting continued week after week, the group discovered numerous previously misunderstood figures of speech. At that point, I became a helpful resource person in the group. After understanding the meaning of the biblical metaphor, the group would then translate that metaphor accurately, clearly, and naturally. The group would then own the new oral story and they were eager to share it with their own families and neighbors. 1 Charles Kraft, Communication Theory for Christian Witness (Abingdon: Nashville, 1960), 112-13 is referenced by David Hesselgrave, Communicating Christ Cross-Culturally 2nd Edition (Zondervan: Grand Rapids, MI, 1991) 63. 2 David K. Berlo, The Process of Communication: An Introduction to Theory and Practice (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1960) 7-10. Dr. Stan Wafler PhDStan and his wife, Pam, lived in Arua, Uganda, from 2001-2015. They served in a variety disciple-making roles, including Bible translation consulting, orality training, pastor training, marriage encouragement ministry, expository preaching training, and student ministry. I would like to invite you to join me on my African journey of engaging language and culture. The journey was full of challenges and victories. The investment of becoming an intentional student of language and culture was well worth the effort. My desire is that you may benefit from some of the lessons I learned along the way.

One rite of passage to become an effective missionary is language and culture learning. Language and culture learning may take place in a structured classroom setting or with informal local tutors. The language learning reality often seems to be a combination of the above. Regardless of the learning environment the attitude of the learner and awareness of the opportunities afforded him are critical. There is a definite journey from confidence in your home culture to humility in your new target culture that sets the stage for effective ministry and growing confidence. My own journey was enhanced by an introduction to orality before I went to the field and orality sensitive mentoring along the way. I served in various church staff roles and as a senior pastor before we were appointed to serve in East Africa in 2000. I remember the uncomfortable thought of my own uselessness dawning on me about six weeks into our African adventure. Virtually everything about my identity failed to transfer to my new African context. I realized within the short time of two international flights I had been reduced to a mere childlike proficiency in the most basic task areas. I needed instructions about bathing and buying tomatoes, washing clothes, and transportation. I experienced the vulnerability that comes with realizing I needed toilet training as well. What I had known in my former life seemed irrelevant in my new African setting. One morning as I woke up in central Tanzania and looked out of my tent, I realized that I was living in a place where my proficiencies were extremely limited. Recognizing my own uselessness was actually helpful for the process I call role surrender. For me role surrender meant setting aside my previous proficiencies, confidence, credentials, and yes even my pride to decide to become a humble learner. This was a painful but significant valley that led to opportunities to discover a new identity and new proficiencies based on language and culture learning. I cannot speak of painful adjustments made for the sake of culture and language without mentioning the model of Jesus, the ultimate missionary. Philippians describes the purposeful but painful descent of Jesus to leave behind his rightful role as Lord of the universe, enter our world, and participate in our culture and language in order to communicate. "Have this mind among yourselves, which is yours in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, by taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men. And being found in human form, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross." (Philippians 2:5-8) One of the ways Jesus accommodated his audience was to engage the oral culture in which he lived. Of course, Jesus could have chosen any communication style but more often than not he employed narratives, asked questions, and recited parables (Mark 4:34). Rather than delivering lofty lectures on theology, Jesus connected with His audience by teaching truth using stories from daily life. The model of Jesus motivated me to consider setting aside my comfort, my communication preferences and my literate expositional style. The choice to start thinking about the oral preference learners around me was presented to me by passionate mentors who demonstrated the use of oral methods at home and in ministry settings. With these models in view, I began discipling my children with oral Bible stories in the evenings. I also decided I would take each invitation offered me to share, speak, or preach as an opportunity to model telling a story from God’s Word. Once I realized that I could not maintain my familiar home culture role and that I needed to discover the new role I needed to fill in my target culture two significant questions arose: 1) What do I need to learn? 2) How do I learn it? When you are entering a new culture you need to learn to communicate but equally important is the task of learning who you are communicating with and how to build relational bridges for your message. You might say that you could make this massive transition from the person you used to be to the person you are trying to become by employing only literate communication patterns and disregarding the notion of orality. However, there were certain benefits to be gained from choosing to acknowledge and engage the oral preference culture around me. Orality became like a new cultural language pattern for me that opened up new worlds of discovery. Awareness of the oral culture around me allowed me to see opportunities to become a learner and listener and set aside my previous role as an expert outsider. Orality provided opportunities for learning, participation, contextualization, interpretation, creativity, and the discovery of the uniqueness and beauty of the local language. After laying this basic foundation, next time I will share some practical applications to the ways that oral methodologies provided various opportunities for communication that encourages going deeper in a local language and culture. |

Archives

October 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed